“Till Death do us Part” – Introduction to the Laws of Marriage

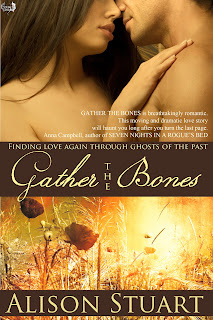

Alison Stuart

*This article originally posted here.

The laws of marriage went

beyond being merely a civil contract, they significantly altered the status of

an individual (the woman) in respect of her actions, obligations and property.

Because it was also considered a "holy estate", canon law as

well as civil law had to be taken into account. Until the nineteenth century,

questions of "Marriage" were the almost exclusive jurisdiction of the

Church.

Marriage required not

only the solemnisation provided by the church but also the "physical union

of man and woman in carnal copulation" (and because I love latin legal

maxims, here's the maxim for the day "commixtio sexuum"). Because

there could be copulation without marriage, it was decided that an intention to

marry (a mental element) had to be present and according to Canon Law (and at

least until 1753) a promise to marry someone could be held as an indissoluble

union, a contract of marriage between two people by consent alone without any

form of ecclesiastical ceremony, provided the consent was given in words of the

present tense...”I am marrying you...” as opposed to “...I will marry you...”.

These irregular marriages were generally legitimised by the parties being

compelled to solemnise their marriage publicly at the door of the church. In

the event of a dispute with a later marriage, this irregular marriage would be

upheld. This archaic concept of marriage lingered through to the 1970s in the

form of an action for “breach of promise of marriage”.

For a marriage to be

“regular”, publicity of the intention to marry came into formal existence by

1200 when Archbishop Walter required banns to be published on three separate

occasions. The calling of banns allowed the congregation to declare any

impediment to the marriage such as consanguinity or pre contract.

In these early days, the

marriage took place at the door of the church. The priest would call on the

couple to declare any impediment. The parties would then speak the words of

betrothal and present matrimony and the husband would then place a ring of the

wife’s finger (the wearing of wedding ring by a man is a modern concept) and

deliver to her the tokens representing dower (see my last blog). The ceremony

would conclude with a nuptial mass inside the church.

In 1753 Lord Hardwicke’s

Act abolished secret marriages. The publication of banns, the purchase of a

licence, the presence of two witnesses and the recording of the marriage in a

public register were made compulsory. Interestingly Jews and Quakers were

exempt from this Act and there was no special provision for Roman Catholics and

non conformists. This was not remedied until 1836 when the civil marriage

ceremony was introduced and Non conformist places of worship could be

registered under that statute.

Husband and wife were

seen in the eyes of both canon and common law as one person (here comes another

legal maxim: erunt animae duae in carne una). This one person was,

of course, the husband. Modern women may cringe at this quote from Blackelocke "...the very being or legal existence of a

woman is suspended during marriage, or at least is incorporated and

consolidated into that of the husband...". Of course the origin of this is scriptual,

reflecting the Canon Law influence on marriage.

A wife could not own

property or enter into contracts. Only acting as an agent for her husband

could she make valid contracts. Married women were only given the same

contractual rights as men as late as 1935.

A wife could not own

property or enter into contracts. Only acting as an agent for her husband

could she make valid contracts. Married women were only given the same

contractual rights as men as late as 1935.

Neither could she sue or

be sued and nor could she take any legal action against her husband because

they were seen to be “one person”. In the case of injury to the wife, a

husband could sue for loss he suffered through the loss of the wife’s services

or society (consortium). He could sue in trespass against a man who committed

adultery with his wife. If the wife absconded with her lover, an action for

“enticement” could be brought against the lover, alleging the defendant had

maliciously schemed to deprive him of his wife’s consortium by enticing her

away. This action was not abolished until 1970! No corresponding rights existed

for the wife.

On marriage any property

which the woman owned as a single woman became the husbands and could be

disposed of by him without recourse. You may recall from my last post, if

the husband predeceased the wife she could claim one third of his estate if he

died intestate (without a will). If he died testate (with a will) she was only

entitled to whatever legacies he saw fit to leave her. Interestingly although a

wife’s real property brought by her into the marriage, vested in her husband

during the marriage, if she predeceased him he was only entitled to a tenancy

by the courtesy. A husband could dispose of her property but on his death the

wife would be entitled to claim it back. However if she wanted to alienate the

land during her husband’s life time, she would have to have his assent. Any

grants of property to the wife during the marriage, vested the property in the

husband.

By the eighteenth

century an equitable doctrine of "separate use" had begun to be used.

In equity, a husband and wife could be seen as separate people and property

settled on the wife during marriage could be held on trust for the wife's

separate use. Judges noted with concern that this could lead to the wife being

coerced into disposing of her equitable estate to her husband and a far

thinking judge solved the problem by inserting "the restraint on

anticipation" condition into a settlement which prevented the wife from

alienating or charging the property during her marriage. This protected the

property for the wife until widowhood. It also prevented her from disposing of

it legitimately in any other form!

While this equitable

doctrine applied nicely to the landed classes, it did nothing for the poorer

classes. By the middle nineteenth century, after intensive

lobbying, the equitable doctrine of separate use was extended to wages and

earnings of working women. This provided some modest protection for those women

who worked to keep their families together only to have their husbands take

their humble earnings. A further reform in 1882 extended this to property of a

married woman, whether acquired before or after a marriage.

Reference: An

Introduction to English Legal History: J.H. Baker

Alison Stuart is an award winning

Australian writer of historicals with heart.

Whether duelling with dashing cavaliers or waywards ghosts, her books

provide a reader with a meaty plot and characters who have to strive against

adversity, always with the promise of happiness together. Alison is a lapsed lawyer

who has worked in the military and fire service, which may explain a

predisposition to soldier heroes. She

lives with her own personal hero and two needy cats and likes nothing more than

a stiff gin and tonic and a walk along the sea front of her home town. She loves to hear from her readers and can be

found at her website, facebook,

twitter and Goodreads.

Her latest book, GATHER THE BONES, is a “Downton Abbeyesque” haunting love

story set in 1923.

2 comments:

So happy the laws have changed! Thanks for the in-depth research.

Thanks for your comment, Sarah. If you think marriage was bad, wait till you read the next post on divorce!

Post a Comment